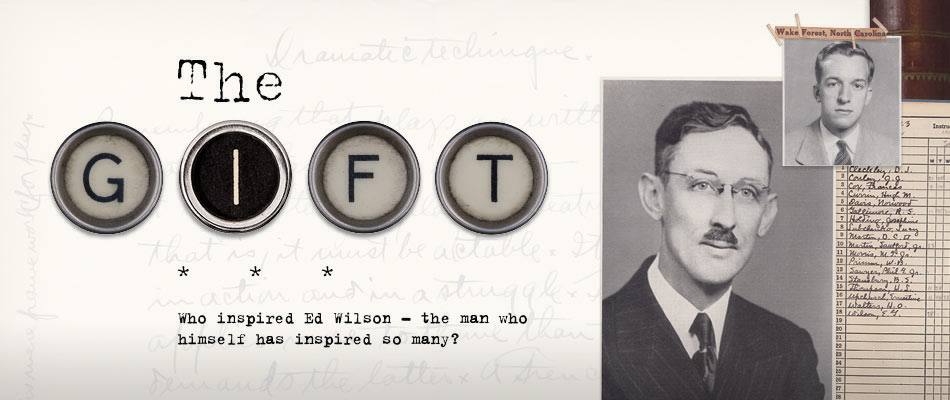

The Gift

BY ELAINE TOOLEY

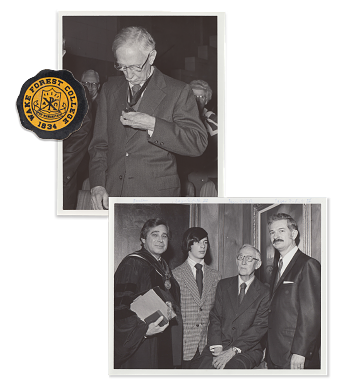

PHOTOGRAPHY BY KEN BENNETT

Known to many as the voice, the face, the steward – the very conscience – of Wake Forest University, Provost Emeritus Dr. Edwin Wilson speaks as an authority on the history of our school while simultaneously inspiring generations of fresh-faced Wake Foresters. In Wilson’s classroom, students were never merely observers. He invited them into his world, and asked to be invited into theirs. It was a genuine invitation. After all, that was his experience as a Wake Forest student.

It is impossible to step on this campus without feeling his influence, and his impact is obvious. But the question remains: Who inspired Ed Wilson — the man who himself has inspired so many?

To some, he was “the Good Doctor.” Others knew him as “Cap’n Eddie.” He was described in one student publication as “the chief Wake Forest apostle of Geoffrey Chaucer,” and some just called him the “master teacher.” He was stick thin, usually wore a tweed jacket with contrasting slacks and broke in each of his new pipes with a Hershey chocolate bar. It is said he had a soft voice, a nervous cough that he unleashed just before he was going to say something important and the uncanny ability to convince his students that the stars were within reach. His name was Dr. Edgar E. Folk, Jr.

He was a third-generation Wake Forester who graduated in 1921 and found his first career as a journalist. That dream took him to New York City, where he spent several years honing his skills as a writer and reporter.

“As a newspaperman on the New York Herald, he had observed and recorded the day-to-day life of the city, with all its variety and excitement,” Wilson recalled. “Throughout the formative years of the 1920s and 1930s, he had seen plays by dramatists, like Eugene O’Neill, who were shaping a new American theatre, and read books by men like Joyce and Faulkner and Hemingway who were redefining the possibilities of the modern novel.”

After some years spent following his beat and absorbing the city’s culture, he decided to return to the classroom — this time as the professor. With a master’s degree from Columbia University and a doctorate from George Peabody College, Folk taught at Mercer University and Oklahoma Baptist University before following his heart back to Wake Forest in 1936.

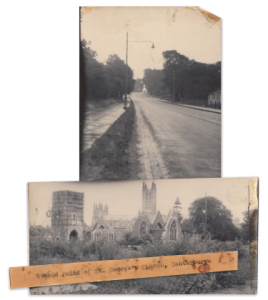

As a member of the English department faculty, Folk was best known for taking his students on a pilgrimage from London to Canterbury with Chaucer, whom the Good Doctor considered “the master journalist.” Folk, enamored with Canterbury Tales, went to England and walked the 60-mile route recorded in the piece so he could more fully describe to his students the bridges, streams, forests and inns that he encountered along the journey.

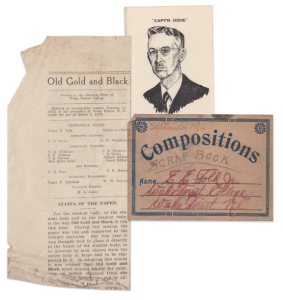

He was appointed advisor to student publications, and built a reputation of excellence when his students repeatedly earned national recognition with the highest honors in collegiate journalism. Some thought he must have been displeased with a few things said in the student publications over his tenure, but Folk insisted on freedom for the publications, and gave his students the genuine opportunity to learn from their actions, saying, “It is better to tolerate errors of judgment rather than turn out namby-pamby yes-men as journalists.”

Among his greatest contributions to Wake Forest was his creation of the journalism program. Folk ardently insisted, to students and faculty alike, that the courses in that discipline remain basic. He believed that all aspiring journalists must engage in a liberal education — full of history, politics, literature, the sciences, math, art, philosophy and psychology — so they would be well-rounded and able to speak on a multitude of subjects.

Just a few years into his 31-year tenure at Wake Forest, Folk encountered a bright and articulate young student by the name of Ed Wilson. As a 16-year-old, Wilson enrolled at Wake Forest, and from that first autumn day, the English and history major from Eden, N.C., wasted little time. He found refuge in soaking up his courses and returning his efforts to the campus community through his work on publications. It was a daunting task. He attended Wake Forest in the middle of World War II, and his work as a columnist for Old Gold and Black and editor of The Howler, under the tutelage of newspaperman Folk, chronicled life in the midst of turmoil. And as the world was struggling with conflict, the young Wilson found peace in the classrooms — and that newspaper office — learning from a soft-spoken scholar.

“He was a remarkable teacher,” Wilson reflected. “His students at Wake Forest were to become his eager followers through the streets and pages of America; because of him they heard about — and read — Strange Interlude, A Farewell to Arms, The Grapes of Wrath, An American Tragedy.

“It’s almost impossible to explain why he was such a good teacher,” Wilson continued. “He had a way of communicating with the class, but at the same time communicating individually with every student. It’s a mysterious quality that I’ve seldom encountered. But he had that. He came to know every student from almost the beginning. What Dr. Folk had that was so special was a deep personal interest in every student who came his way.”

Folk was also quick to determine the gifts and assess the limitations of each student in his classes. He would praise the strengths and point out where a student could use more attention. “He had a way of probing and finding out what you needed,” Wilson said. “He always had a personal suggestion to make for each student. Therefore, his teaching ability is immeasurable in that you can’t quite explain to anybody — unless he was there — what it was like.”

The demand for excellence was also ever present within his classroom. “Woe be unto us if we misplaced a comma or wrote a fuzzy sentence,” recalled the late Bynum Shaw (’48), a former student of Folk’s. “He insisted on good, clear writing, and taxed us terribly until we could turn out a coherent paragraph. Above all else, he had one special quality: the ability to inspire. He could get us so fired up about journalism that we couldn’t wait to go out and conquer the world with a typewriter and a sheet of newsprint.”

In 1941, after only a handful of years as a member of the faculty, Dr. Folk was so well loved by his students that they dedicated The Howler to him. “The use of words, at best, is clumsy when we set out even to suggest the role that Dr. Folk has played as a member of the faculty here,” the inscription reads. As an adviser to the University’s publications, “he offered hours in time, days of work and worry, and the door of his office has never been closed to students who seek earnestly to find new threads of finer journalism in a baffling era … indeed, he personifies the enviable characteristics associated with brilliance in scholarship and leadership; yet we like best to think of him as a newspaperman who has given his all to assist us in interpreting for ourselves the often-confusing story of life.”

Folk did not just teach English; he taught students to love what he loved. He had captured his passion and was helpless to do anything but pass it along to those who entered his life.

“The secret of Dr. Folk’s success as a teacher was not primarily in his learning, considerable though it was, or in the traditional talents of the pedagogue,” commented Wilson. “His strength lay in his casualness, his ease, the way in which he could hint or suggest, his patience, his very reluctance to assume authority. Most of us, I suspect, remember less than we should of what he said; rather we recall his look, his presence, his humanity — his character. Like Chaucer’s knight — I hope Dr. Folk would forgive the modernization — he loved ‘chivalry, truth and honor, freedom and courtesy.’”

On more than one occasion, Folk’s students became his friends. And, as any good friend, Folk didn’t forsake them once they graduated. “When I was in the Navy, Dr. Folk would send me postcards,” Wilson explained. “And, I’m sure he did that to the others. But, I would occasionally — out in the Pacific — get a postcard in the mail from Dr. Folk. ‘How are you getting along? Let me tell you what’s happening at Wake Forest.’”

Not only was he loved by his students, Folk was a trusted friend of his colleagues. The man of character served as a wise counsel to and confidant of President Scales. “Long before most Wake Forest men and women came to this place, Mrs. Scales and I were introduced to Wake Forest College by a master teacher who was himself an alumnus, the very embodiment of the values we came to associate with Wake Forest,” he wrote about Folk. “To be in his literature classes, to study for the first time the Greek and early English classics, was an inspiring moment in our lives. To be a student editor advised by this wise and witty journalist was particularly rare. The voice was soft, but reproof for slovenly writing was prompt and hard. Somehow the experience confirmed our passion for that imperishable heritage we call ‘freedom of the press.’

“Tennyson said that when the Knights of the Round Table listened to King Arthur speak on matters nearest his heart, there came over their countenances the momentary likeness of their King. That was the kind of encounter generations of students, east and west, had with Edgar Estes Folk.”

At his funeral at the old Wake Forest Chapel — in the town that would forever be Folk’s home — Wilson offered remarks about his mentor and friend, the one who helped shape him as a student, a professor and a person.

“For Dr. Folk, the beloved past and the vibrant present met in the classroom and in those college publications offices where students who perhaps loved him most gathered to listen, to ask and answer questions, and to write. He was a master teacher. We who were his students know that because of our own grateful memories; if we respect words and if we respect truth, we do so in part because he taught us that they are linked irrevocably. Those among us who were not his students should know that in newspaper offices and college classrooms all over the country there are Wake Forest men and women who came to where they are because something Dr. Folk once said made them write better or think more clearly or act more responsibly.”

Wilson taught decades of students, welcoming each with open arms to the promise of their future. He unveiled the intricacies of works by William Butler Yeats, William Wordsworth and John Keats while sharing personal accounts of hearing Robert Frost and T.S. Eliot read their poetry firsthand. Peppered in between questions his students asked of him, he volleyed back his own — wishing to know the young men and women who joined him in the learning experience. As an educator, Wilson knew that it was his responsibility to nurture the young minds he taught, and to look after each individual entrusted to his care.

Maybe it is the tweed jacket of Folk or the charming Southern accent of Wilson that their students remember when either man’s name is uttered. Perhaps it is the tales of Chaucer or the poems of Yeats that come to mind. More than likely, it is the kind commitment these men had to their shared discipline that their students recall. Unequivocally, these men are remembered as friends who dared to use their gift of inspiring others to make everyone who entered their worlds a little better.